Talking Ed: Kevin Thatcher Interview

2/24/2021

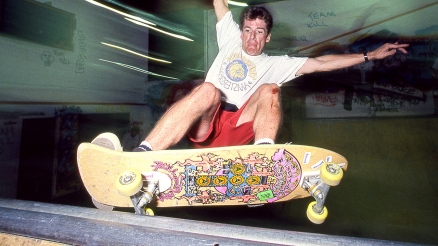

Photo: Mofo

Photo: Mofo

Kevin Thatcher, or KT as he’s known, was Thrasher’s first Editor in Chief from its birth in 1981 until Jake Phelps took the reins in 1993. He’s the original T-Eddy, designed our infamous logo, shot covers, wrote articles, made artwork and helped define the Thrasher ethos while steering the ship from skateboarding’s dark days into the modern age. This interview is long overdue. Thanks, KT!

As seen in the January 2021 issue

So you were a pro skater first?

I was a pro skateboarder for about five minutes. I had a couple placings skating against heroes of mine like Brad Bowman, Alva and Doug Saladino at Winchester. I think I was favored by the judges. I got 8th place behind Brad Bowman once. To be skating side-by-side with these guys was a thrill. My friend Rick Blackhart was discovered and I was almost like his valet. I made boards for him. I would set them up. I would drive to the spots. Pretty soon he took off. He was an unbelievable skater. Meanwhile, I was back working at the Tunnel factory. To be a pro back then, you would work at the warehouse during the day, work at the retail store in the afternoon and go to the skatepark and practice in the evening. It was a working-man’s existence, not some kind of superstar trip. I had a camera and I was taking photos. My training for the magazine and to be able to publish Thrasher was as a graphic designer and artist. Back then graphic arts were not on the computer. It was all paste up and halftones, photography and airbrushing photos. Learning all of those skills was really cool. It was really organic.

How did you learn how to do all of that stuff?

I worked for a graphic artist who gave me a job out of high school. They taught me paste up. It’s hard to even describe now. You wrote a story, typed the story, sent it to the type setter. They sent back galleys, which were long ribbons of typography. You cut it out, paste it down on a board next to the photos, or a black square where the photo is going to go. Then you shoot negatives of everything. The printer would strip it all together and insert all of the photos and artwork. They would make plates and hang them on a press. Basically we started printing on a newspaper press. It would take hours to describe the process. It was primitive. Even back then, color printing was still fairly primitive. If you go back and look at the early issues of National Geographic and Life Magazine in the 1970s and 1980s, the printing is fairly chalky and crude. Color printing was still coming into perfection, not the super gloss that you get these days.

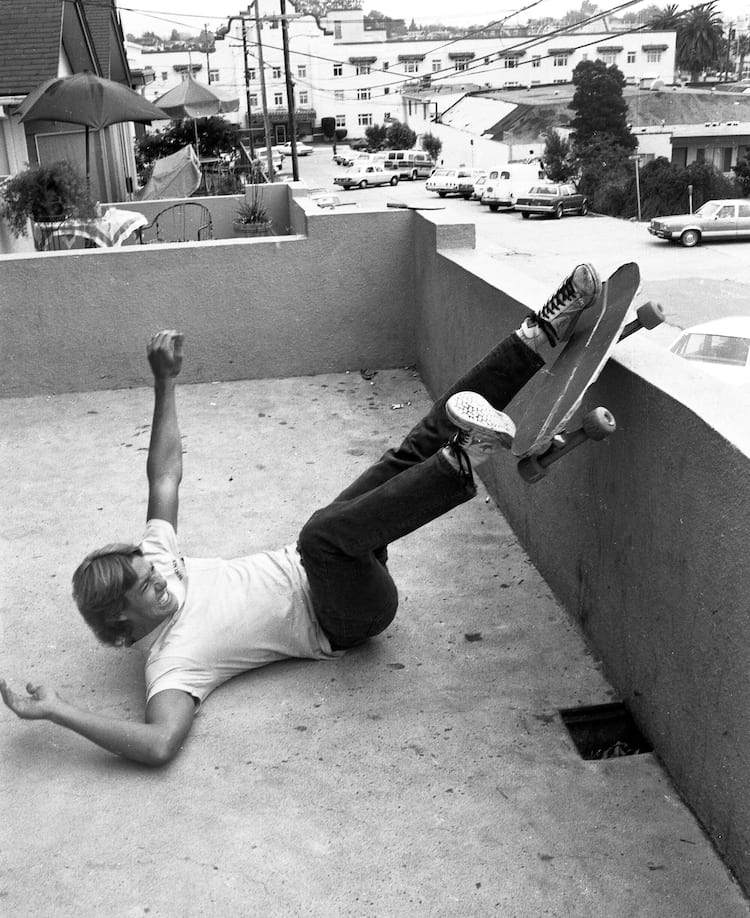

Spine time Down Under / Photo: Needham

Spine time Down Under / Photo: Needham

How did you connect with the people who would become the Thrasher team?

Blackhart and I met up with Fausto and Eric Swenson somehow in Rich Novak’s office. They were kind of struggling to put together Independent trucks. Rick was really opinionated and they were asking us about building a truck. They had a concept. They were motorcycle heads but they were still skaters bombing hills in San Francisco. They used to be the pit crew for the Harley Davidson flat track team. They were asking us about a bunch of stuff and we ended up helping them develop the Independent truck. That’s where the association with Fausto and Eric started. At one point, down the road, we were just hanging out and Fausto came to me and said, “We want to start a magazine.” Skateboarding was dead. The mags at the time were changing or diversifying. Skateboarder Magazine turned into Action Now. They were diversifying into motorcycles or mountain bikes or even horseback riding. That was the last straw, when they published photos of a woman on a horse jumping over a log on the beach as the centerfold. Skateboarding’s boom/bust cycle was at a real low point, but we knew skateboarding was going to be around forever. It was just too cool to let it go. It needed new energy. Of course we had no money. That’s why those first issues started out as practically a newspaper. That’s all we could do. It didn’t need super gloss. It needed attitude. It needed the culture to be brought out that was bubbling underneath the surface. I’ll never forget when Fausto came to me and said, “We’re calling it Thrasher.” Duane Peters came up with the name, “Call it Thrasher, dude.” I wasn’t there. But when Fausto said it, there was no argument. Who’s going to argue with that one? It just works, and it has worked well. It was evident that was it. It didn’t need the term “skate” in there. It was a cultural thing.

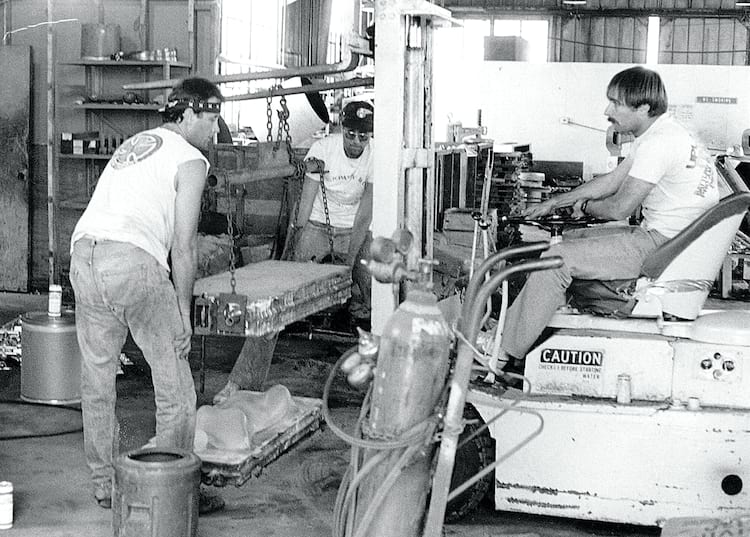

Eric Swenson, C.R. Stecyk and Fausto Vitello making Independent trucks / Photo: Mofo

Eric Swenson, C.R. Stecyk and Fausto Vitello making Independent trucks / Photo: Mofo  Blackhart on some serious R&D / Photo: KT

Blackhart on some serious R&D / Photo: KTHow did the logo get made?

I did the logo. On his way back and forth from Santa Cruz, Fausto would come by my place in Los Gatos and I was coming up with drawings. We were creating a 16-page mock-up of the magazine. It was sketched up with colored markers. I did the logo basically with a press type already-existing letter font. You buy it down at the store or whatever. I redesigned this letterform into the classic masthead. It just worked. There’s been other versions of the Thrasher logo done. I think we even challenged people to come up with something to change the logo but nobody’s ever done a better one. Fausto came by and he picked up the sketched-up artwork version of the magazine. He shopped it around and went to LA and went to the big five companies that were in charge of the whole skate business. Everybody was pretty skeptical about it. I don’t know what happened to that mock-up, but it would be a Smithsonian institute piece of archival history to have. Fausto claimed he misplaced it at some point and never saw it again. That was the start of it.

Did you have an editorial philosophy going into it? Was Thrasher a reaction or an answer to what had happened before it?

I think more than that, it’s going back to really knowing that skateboarding was there and it was going to be there. It was tapping into the energy—that latent energy. It was punk rock. Skateboarding was regional at the time. It wasn’t so much a reaction. The timing was right to do it. We were able to buy in cheap. It didn’t take too much to get the thing out there. I think the first issue we printed, I don’t know, 10,000 copies. The second issue we printed 5,000. All of a sudden distributing that many copies of a magazine, we would end up with some leftovers. It was pretty quiet out there but the energy of skateboarding was so inherently cool that we couldn’t go wrong. Back then there were pockets of skating going on. In Texas, there was the Zorlac crew. Florida, there was John Grigley and Paul Schmitt. The Cherry Hill skatepark was still happening—one of the best skateparks ever in New Jersey. Right away we started to hear from all these crews. Forget about the West Coast. Pretty soon there were pockets in Nebraska and Little Rock, Arkansas. They were out there and that confirmed it. It wasn’t like we needed to be convinced that we were doing the right thing, but you could feel it. More importantly, the skaters in these scenes became our contributors. They helped us make the mag!

Who was the brain trust of Thrasher in the beginning?

When it started I moved up to San Francisco and I remember some of those lonely days. We had our first issue in January of 1981. I started to put together artwork and I had some photos in my file but right away we had to tap into resources. This was going to be a national magazine, worldwide, right? A lot of it came from existing files we had. I was already working on the illustration that would be the first cover. We had photos, but that just seemed like the right thing to do. The first issue tapped into the music aspect. We took some heat for that from the hardcore skate-only people. Part of the skate culture was art, music and fashion. Fashion has gone on to be somewhat of a big influence.

How did you meet Mofo, Thrasher’s first photo editor?

Mofo was around the skatepark in San Jose. I remember him rebuilding his Riviera in the parking lot of Campbell skatepark. Always on his soapbox, he was quite a character. He contacted me a couple issues in and said he had some artwork and some stories. He was always a really creative guy—always way into music and a big influence on the direction we had already taken with the culture. Those “Wild Riders of Boards” that he put in the first issues were classics. There’s lots of different chapters with Mofo. One day he was a cholo, one day he was an American-Indian. He was just a chameleon. He would dress up. For all his cool, he was the nerdiest fucker out there. He was definitely one of the first to come in and sleep on the floor of my apartment with Eric Swenson. We had a darkroom in the closet. It was the rudimentary hand-to-mouth existence, making no money. Mofo and I used to butt heads and stuff about ideas but being an editor of Thrasher there was always about ten percent that I didn’t agree with or like at all. But it wasn’t my magazine; it was a group effort. There were a bunch of ideas coming together. Mofo would challenge me on graphics and writing and I sometimes felt he was doing it just to disagree or to push my buttons. I don’t think any magazine should just be one person’s vision. I think we managed to do that. One of the articles that appeared in the first issues was “Notes from the Underground.” Terry Nails wrote that. He was more of a rock ‘n’ roller who played bass in a chart-topping new wave band. His claim to fame in skating was that he drove the Independent Stroker downhill skate car in Signal Hill in Long Beach. He famously crashed at the bottom of the hill. Later on, the word was out. People started to gravitate towards us and we knew everybody. Bryce Kanights came in that way. I called up Bryce about photos. I knew he was a photographer and skater. He came down and brought his portfolio of photos. Pretty soon he was working at the mag doing paste up and graphic arts. We would drive to our country printer up in Clear Lake, CA, and pick up the mags in the Toyota pickup. We would drive back to Hunters Point shipyard where the mag first started, gather up the local skate crew, wrap up the magazines, stamp them with the postage and do the subscriptions. It was a real grassroots effort with everybody. We coerced the skaters into helping us every month.

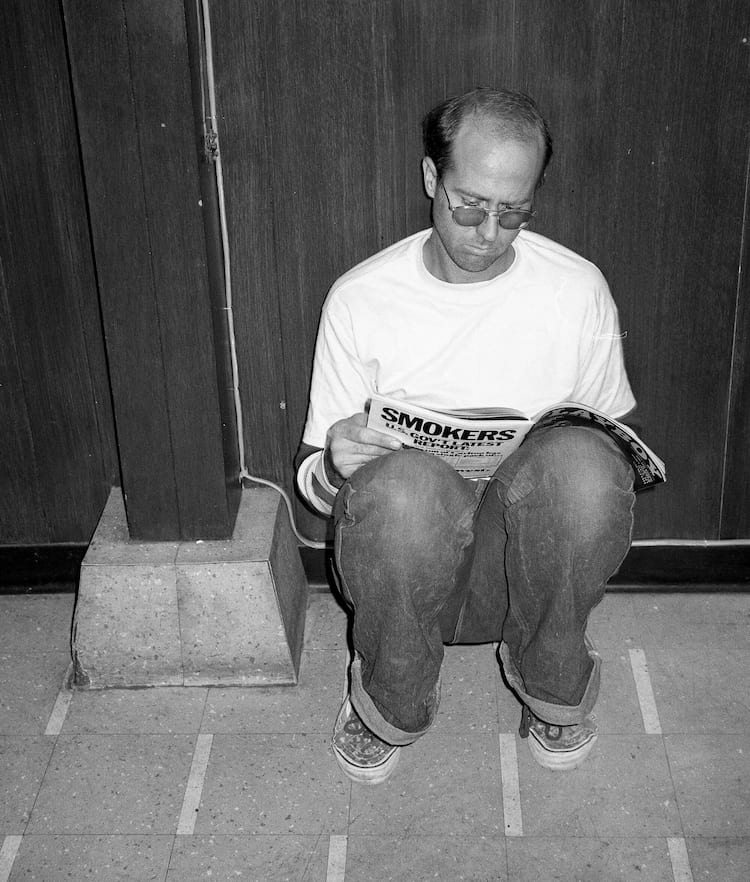

Mofo in his civvies / Photo: KT

Mofo in his civvies / Photo: KTHow did Stecyk get involved? Did he work for everybody back then?

I think he demanded that. That was part of his unwritten contract with the world. He had an association with Stacy and Powell. I think it was okay with everybody across the board. There was a sense of mystery with Craig’s work and his knowledge. Without Craig, all of skateboarding would be without sail. He held it down pretty good.

Cyptic ponderings, C.R. Stecyk / Photo: KT

Cyptic ponderings, C.R. Stecyk / Photo: KTWhat about Pushead?

Just another skater from Boise. There was an association with Glen Friedman. They’ve got heads full of ideas, very talented guys, both of them. For a long time we didn’t use Friedman’s stuff because he was so difficult to work with. We ended up using some of his stuff—he had a couple great covers. He was a great photographer. He was so thrifty, he would talk about wasting one frame of film in a roll, like it was the worst thing to do. It would crack me up. Pushead was contributing letters and drawings to the mag. I think we first published one of his drawings and then later he did the Puszone—his take on the craziest music. It was right up our alley.

What was it like in the office? Were you guys getting in at noon and crushing Coors Lights?

We were smoking cigarettes and the occasional joint would flare up in the office but it was pretty professional. Occasionally Fausto and Mofo would erupt in a wrestling match. There was a certain amount of stress, but it was on the cheap. We didn’t have excess to get out of control. It was a monthly magazine so that deadline comes up pretty quick. Fausto’s drive was just unbelievable, but he did play a pretty hands-off role, as far as editorial influence. Since we were a Northern California company, there was a lot of suspicion that it was tainted. I think we managed to pull energy that we had in Northern California but also spread it throughout the land and prove that we could do something that could represent the skate culture.

Bryce Kanights, business casual at the Ermico office / Photo: KT

Bryce Kanights, business casual at the Ermico office / Photo: KTDo you remember who your first subscriber was?

I used to have an answer for that. I think it might have been Keith Cochrane. Let’s just say that.

Who was an early advertiser that really saved you guys?

Nobody saved us, but Tom Sims. He was difficult to work with, but he didn’t want to miss out on anything. I miss Tom; he’s one of the guys that has passed along. He took the back cover and he knew the value of being out there and being involved. It wasn’t so much about getting money for an ad as it was the artwork. When you’re trying to fill up pages—the mag was 32 pages—it was always a big thrill to get the artwork for the ad, especially if you get actual negatives or something that was prepared by a real graphic artist. Santa Cruz was right there—they were supportive from the get go. They were also the biggest complainers when they didn’t get coverage.

What was the rate for a full-page ad in the beginning?

Let’s just say in the hundreds.

As you were learning to make a magazine, were there any really shocking errors you made?

We made mistakes. The time we covered the Pomona contest we spelled Pomona wrong in 32 point type. That was pretty good. You get away with it. Just like we got away with tweaking the English language. We were not English majors making a literary masterpiece. We were cutting it up pretty good and getting away with a lot. We used to send Mofo on the Greyhound bus to Del Mar to cover the contests. It would take him a day and a half to get there and a day and a half to get back. He would end up writing the article more about the bus ride and the burritos he would roll up at the end of the trip. He would come back with hardly any writing about the contest itself, which was the classic gonzo/Hunter S. Thompson style. You go to cover a contest and never even make it to the contest, but here’s the story anyway. That became sort of a trademark of not only Thrasher but the Mofo style. We would get the letters to the editors like, “Goddamn! He wrote more about the burritos than he did about the contest!” The contest? Yeah, whatever. They get boring. Who cares.

Where did the name T-Ed come from?

Well, first it was my intro to the mag, “Talking Editor.” Then it was T-Ed. One of my nicknames was Ted. Then later Jake made it into the awards. It just happened.

I’ve always wondered: was the “Caution: Contains 100% Aggression Inside” cover on purpose, or did you not have a photo that month?

I think the aggression could be related to not having a photo. I mean, we were swimming in photos, how could you not have a photo? There were more than a few times where we would come home from a contest and we wouldn’t have a good photo of the winner. There were some cover photos you could argue were shitty photos. There were a few blurry ones. The photographer would talk us into it being “art” and we’d go with it. I have a problem with the cover photos these days. The skater is so small in the photo even though he’s doing a 30-stair gap. On the newsstand at Safeway or whatever, you could barely see the photo. Try a photo with a truck grinding on coping and in the background maybe you see the skater’s eye. So close up and so intense. That’s a cover!

Yeah, we definitely have the burden of massive terrain. Do you have a favorite cover from the early days that you felt like really represents the mag?

I took a few covers in my day. Those covers are the ones we waited until the last possible day to get the photo. One of them was Tommy at Fort Miley. I called up Tommy and we went out and got a cover shot. It was golden hour at sunset and Tommy going off these little Miley banks. I tended to really like the full-bleed photo with the logo. When it comes down to it, for a magazine, I thought those were the ones that worked—big skater, big pop, good color. I thought those were the best. I still do.

Who were your favorite skaters to photograph and travel with?

I have one roll of film of an empty pool over here in San Jose. I invited Caballero and Mark Rogowski to skate this pool. It was like five feet of pure vert. Mofo was there, too. They were both ripping this ugly pool. Every photo of Gator is just sick. Cab, Gator and Christian. Christian could skate anything. He was so eager, and a showoff. The photo of Gator became our first color cover.

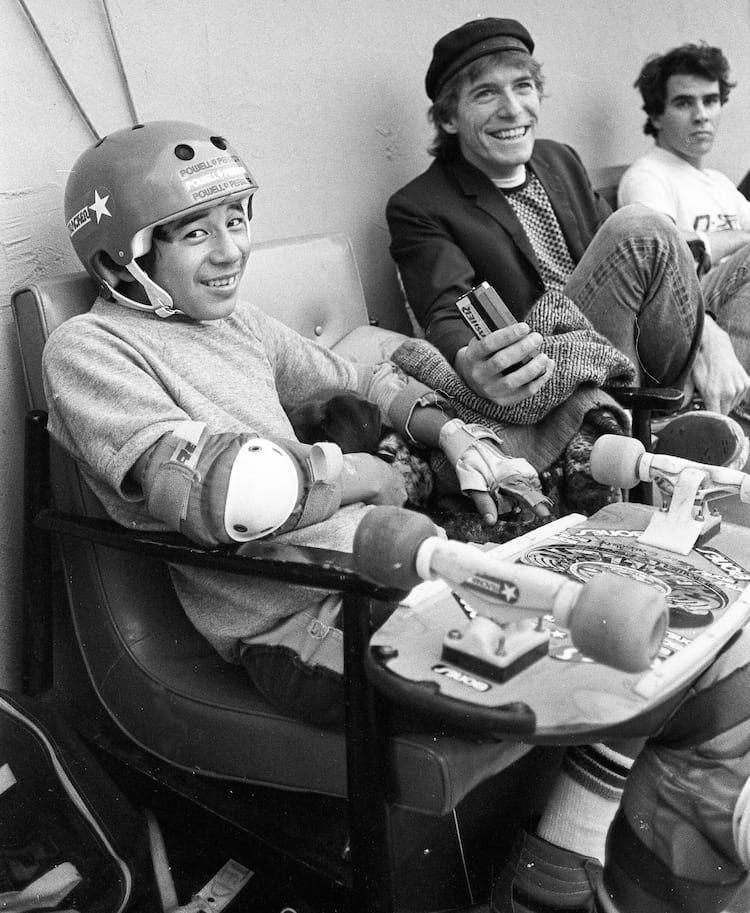

Stevie Cab in the hot seat, 1981 / Photo: Mofo

Stevie Cab in the hot seat, 1981 / Photo: MofoThrasher famously took skateboarding on the road with events like the Midwest Melee, The Great Desert Ramp Battle and Savannah Slamma. Why was that important?

We have to give credit to Fausto’s vision. He would turn it over to us to do what we would. There were strong scenes in these little places. It wasn’t this West Coast-surfer thing. It was really a diverse crowd and we tapped into that energy out there. Plus, we needed to make shit happen so we’d have stuff to put in the mag! Bringing Christian and Roskopp and those guys out to Lincoln, Nebraska, was great to see how excited people would get. People wouldn’t believe these guys were coming to their town. To be able to do that was cool.

The Midwest Melee(s) brought the pros to the Heartland. Monty Nolder stalls one in Rich Flowerday’s backyard, 1984 / Photo: Mofo

The Midwest Melee(s) brought the pros to the Heartland. Monty Nolder stalls one in Rich Flowerday’s backyard, 1984 / Photo: MofoWhy did you guys pick Savannah, Georgia, to do one of the first pro street contests?

Tim Malin’s family ran a local skateshop, High Tide, and his father was a country club guy and well connected. He had the MLK arena in Savannah, Georgia, available and an in with the lumber company so we would get the supplies for cheap. We had been doing Joe’s Ramp Jam and the Road Show, stuff like that. It just worked out. We’d show up with Red Dog, Lance and the crew and build the course three days before the contest. Fausto was wielding a hammer. We didn’t know what we were doing, but we did it. We built a quarterpipe that went up the wall with 15 feet of vert! We would be so hungover and burnt after building everything and then show up to the contest the next morning with a line around the block with people waiting to get in. It was pretty cool. We sold that place out, I think, three years in a row.

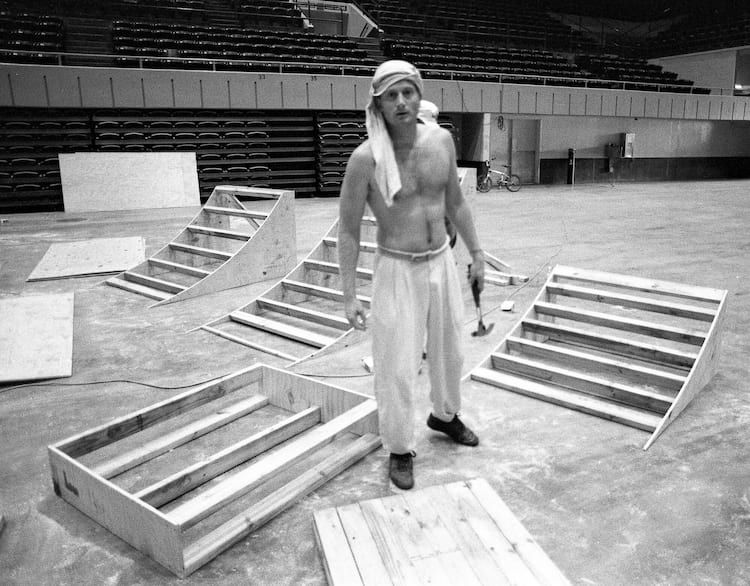

Hammer time! Stacy Peralta pitches in at Savannah Slamma, 1987 / Photo: KT

Hammer time! Stacy Peralta pitches in at Savannah Slamma, 1987 / Photo: KTWhat was the real story of Transworld starting, from your perspective? Was it Thrasher’s filthy advertisements and the Skate and Destroy article?

That probably had a lot to do with it. I think they might have seen an opening from the business perspective. I think they came out with color printing before we started doing color. Which at that time it still didn’t really matter to us to be full color. One of the great stories—the first issues of Thrasher we would get complaints that someone’s girlfriend—the ink would rub off on her white pants or something. All the ink was rubbing off on her clothes and got her all filthy. We thought that was cool. It was pretty funny. I guess my point is—Thrasher was pretty crude. We were like a newsprint, pretty raw. Skate and Destroy and that Indy ad that pretty much showed a bare breast—the Tracker people didn’t like that. I think that was one of the first Indy ads Stecyk created. There was also the classic Roskopp ad with the girl bent over. Pretty ugly photo, I might add. When I said I wasn’t in agreement with everything in the magazine, that would have to be one of them. I would call Novak and say, “Are you sure? Really?” I think the Tracker guys, they had a chip on their shoulder. The San Diego contingency always had a bone to pick with everything. The original North/South battle was LA versus San Diego. Then it was So-Cal vs Nor-Cal. So they started their own magazine.

Did them creating another magazine cause ripples in what you were doing?

Competition is healthy, especially in business. I think at one point there were six skateboarding magazines out there.

When were there some signs of skateboarding picking up and becoming a real business?

By 1986 when Vision, Powell, Santa Cruz, Sims, the big five were happening. Skateboarding was huge again. There’s a ten-year cycle. A real progression and revolution started to happen. All of a sudden a whole new crew comes up and starts blowing everyone’s mind.

How big did the circulation get in the ’80s?

Pretty big. Some of it is driven by numbers, but sometimes the numbers lie. It’s kind of like the record industry. A gold record means there were orders for records but not a lot of sales. You can ship a lot of magazines but a lot of them get returned. A magazine in somebody’s hand is a whole different thing.

Did it feel like it was becoming more of a real business towards the late ’80s?

At times. There was a lot of money to be made but there was a lot of overhead—especially shipping a box of magazines. The thing weighs 50 pounds. It gets into a whole lot of business talk. My claim as the best-selling cover ever was when we put the skybar above the logo that said, “Bart Simpson sells out.” There’s a little image of Bart Simpson. Probably late ’80s or early ’90s. I was like, “Ed, you want to sell some magazines? Let’s put Bart Simpson on the cover.” The Simpsons were going off. It was huge. It was also when we were selling a shit ton of magazines.

What was the decision to start the Skater of the Year award in 1990?

I don’t remember. Probably the first one was my idea when it was Tony Hawk. The first award was this crude sculpture.

I have it! Tony gave it to me last week.

Really? Yeah, some of the decisions we made were really on a whim. Like Slap. I was working late at the office and Fausto was there. We had an idea to create our own competition. I remember within 45 minutes we had a flyer and we were faxing it to, like, 35 companies, announcing the new magazine. We put Lance Dawes in charge of it the next day.

The first SOTY issue is Tony Hawk—guy in the sky, no coping, melon to fakie with a silver background. Was that really a best seller?

That’s the truth. It also won an award from this publishing board. They sent our art director to New York City. Another cover that won an award was the 100th issue, the John Hutson downhill. That was the first cover with varnish on it. Downhill, wearing skin-tight wetsuits or whatever. Thrasher was instrumental, not only for skateboard magazines, but in magazine publishing. We were noted in some of the trade magazines at the time for desktop publishing and computer graphics we were doing. Ken McGuire came in. He was a little flashy but he really excelled working at the mag. He brought us up in the world of computer graphics and desktop publishing. We had some of the first in-house typesetting equipment, eventually all of the Mac stuff, Quark and Photoshop. We were right on top of that.

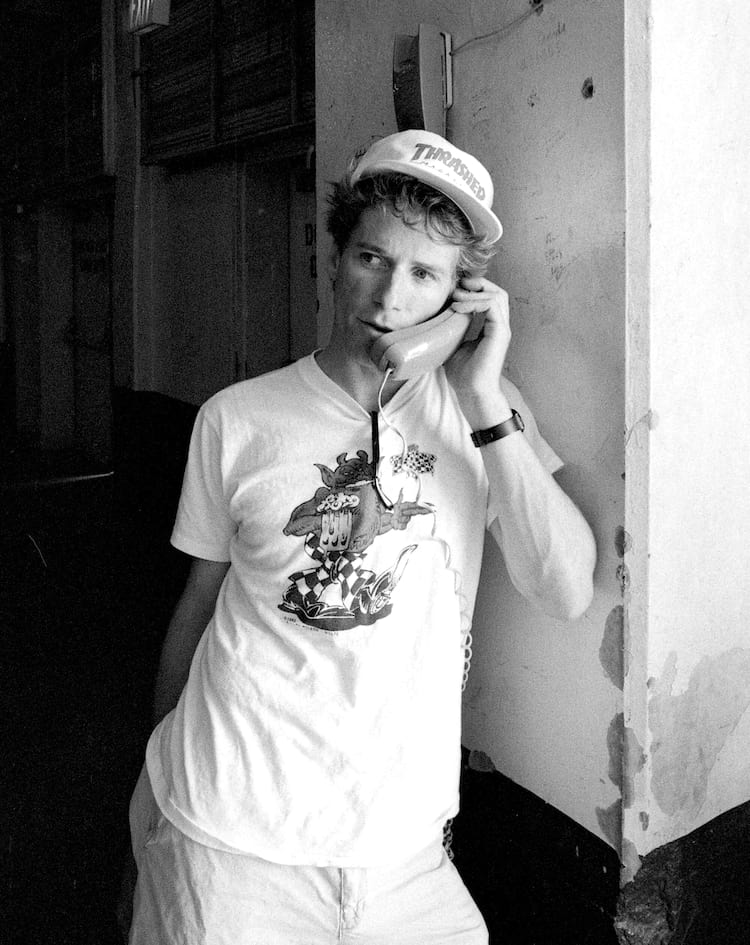

Taking care of business. No roaming charges here

Taking care of business. No roaming charges here KT and Blackhart, 2013 / Photo: Brook

KT and Blackhart, 2013 / Photo: Brook Publisher Ed Riggins and KT, “launch break” in 1989. Better get ready for those 90s, boys! / Photo: Mofo

Publisher Ed Riggins and KT, “launch break” in 1989. Better get ready for those 90s, boys! / Photo: MofoWhat was the vibe at the mag, heading out of the ’80s and into the lean years of the early ’90s?

What a cool era. Jovontae and Mikey Carroll, Guy Mariano, the Embarcadero scene—so under the radar. The business of skateboarding and mag sales were really low. We were down to 56 pages or something. The mag was lean and mean. We had nothin’ as far as advertising. I’ve followed a lot of magazines and seen a lot come and go. The newsstand is getting pretty short. To see Thrasher out there still in print is pretty cool. When I was still editor and Jake was right there, we got caught off guard when the video-capture sequences came out. We got caught flatfooted on that one for a while. There was competition and competition makes you stronger. When Big Brother came out and was making fun of us all the time you just had to stick to your guns and keep doing what you’re doing. There was some complacency at some point. Jake came in when we all became tired; the writing was on the wall. You can’t deny what he did when he stepped in to carry it.

I know you guys had a bond and appreciated each other. What was his effect on the other staff?

There was some struggle there. Jake was a hard ass. He had a sensitive side and he cared. He was good at fucking with people. He couldn’t really bullshit very well—he talked the truth much better than he bullshitted. It’s much easier to remember the truth. It’s a lot harder to remember bullshit. I remember sweating bullets all day when he asked me to come skate his ramp, the Widowmaker. The rule was you had to roll in or get the fuck out. He was harsh, but he got the best out of you. Yeah, I made the roll in!

Did you feel good about handing the reins to Jake?

We were transitioning for awhile. I used to announce contests a lot and it came to a point where I didn’t know the tricks. I had to have a guy next to me telling me. It became obvious that I wasn’t going to be able to keep up. I started getting into publishing duties. I was the editor of Juxtapoz the first couple years of that. I was towing the line and being a publisher. When I finally left the mag, I signed a contract that I wasn’t going to use the name for anything. I promised Fausto and Ed that I wasn’t going to go work for a different skate mag or company. I didn’t want to.

KT, a brick and the Phelper, 1989

KT, a brick and the Phelper, 1989Why has Thrasher lasted for 40 years?

If the mag had any influence it was to get out and skate. Get out and do it! You can do it just as good as we were doing it. It’s not all about the mag. It was purely fueled by the readers and the skaters. Photograffiti and Zine Thing still are the coolest parts of the mag. If anything I said in this interview starts with “I,” change it to “we.” It’s a team that makes it happen; it’s a group effort. One of the great things about it is that the act of skating hasn’t changed a whole lot. The younger kids now, they don’t want to know the history. They want the adventure. The best thing about skateboarding is the adventure and everything that surrounds it. That’s really what works. Everything else can be swept under the rug. People have tried to replace it but it just doesn’t work as well. That’s why Thrasher’s still here.

Are there times where you miss being around skating?

From the very day when I moved up to the City and started working for the mag to the time I left was pretty intense. Stressful in a way, but I’ve traveled the world working for the mag. I could tell a lot of stories. I feel like I had a pretty good run. The mag will speak for itself.

-

Burnout: Waffle 50

Vans celebrates a half century of skate shoe excellence with the first stop of a worldwide tour – NYC. You guys party? -

Cab's 50th B-Day Bash! LP

Beer City is proud to bring you The Faction’s Destroys O.C. – Cab’s 50th Birthday Bash! live LP/DVD. -

Rumble In Ramona 5 Video

Vert skating's favorite event is back! No winners, no losers, (except anyone who chickened out,) this is halfpipe action at its down-and-dirtiest best! -

Rumble In Ramona 5 Photos

Here's some Rumble photos from Ramona to get you fired up for the video coming soon. -

Vans Pool Party 2015: Finals

Broken boards equals broken dreams. Chris Russell had it in the bag but one too many hang-ups enabled Tom Schaar to spin his way to the top. Meanwhile, Pedro Barros stole the show with a death defying NBD. 10 years of the Pool Party and this was the best one yet! Cheers, Vans!